Our primary goal at Smarten Up is to help students become learners. We want them to learn how to read and do math, to learn about the history of our world and the science behind it, and to learn about themselves. To do this, we empower them with a robust set of tools and strategies that they can use to tackle the wide range of challenges they are likely to face in their academic careers and beyond. The key to making this happen is teaching students the difference between “knowing” and “understanding.”

Tests, quizzes, writing assignments, and classroom discussions are tools that teachers use to evaluate how effectively students have learned the material. As we know, assessments range from multiple choice and short answer questions to word problems and essays. The former evaluate a student’s rote knowledge—how well she can recall a definition or perform arithmetic; the latter gauge children’s ability to use information in order to answer a question or solve a problem.

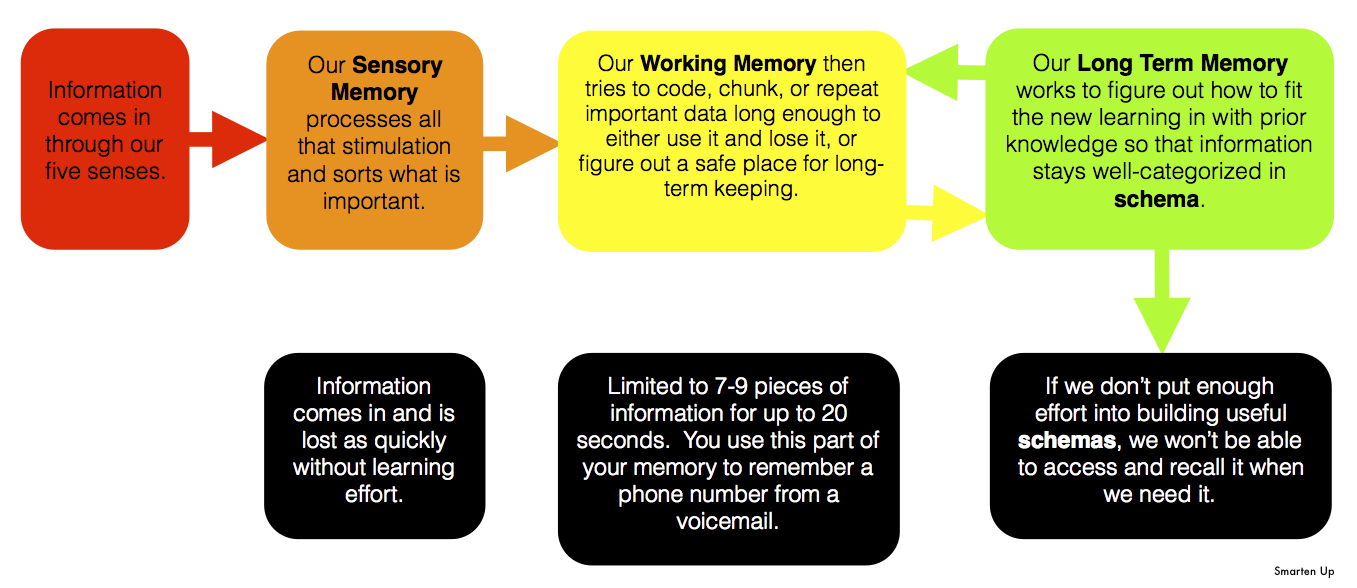

Genuine learning occurs when students can build their understanding of a given concept from the ground up, from knowledge through evaluation. It is the difference between cramming for an assessment by memorizing a collection of vocabulary terms, and learning those words in context, with the support of graphic organizers, outlines, mnemonic devices, and other memory aids. While the latter may take more time and effort before the test, that energy will pay off when it’s time to study for a midterm or final exam. Even if a child doesn’t remember everything, she will have an efficient set of familiar, useful resources to fill in the gaps. By taking the time to learn and understand the information the first time around, students can avoid the chaos and anxiety that comes with last-minute scrambles or disorganized efforts (or both).

This is where it becomes most important for us to teach our students about themselves as learners. We need students to understand the difference between working smart and working hard (or not so hard in some cases). They’ve been told to create outlines before they begin writing an essay, though they often don’t do it. Teachers ask them to annotate as they read, but their books often show either pristinely clean pages or ones that are so filled with highlighted text and underlined sections that they are impossible to navigate. They have to study for a test or quiz, and often they simply reread the relevant information and declare themselves “prepared.” They are told to create a plan of attack for short-term and long-term assignments, and they simply open up their portal to look at what is due the next day.

A large part of this disconnect is due to a lack of understanding. Students know what they should do, but they don’t always understand why or how to make those extra steps meaningful. The goal of Smarten Up’s March blog posts will be to share our favorite tips, tricks, and strategies for helping students learn how to become learners.